The first time I ever saw a Margaret Clarke painting was the day I started as a museum guide. It was a very strange and overwhelming first day, we had just come out of the first lockdown and my new colleagues were as a result much harder to approach than usual with social distancing. The number of visitors were reduced as well so for much of my first day I was left in an empty gallery, excited and grateful to have a job in my field after graduating with a humanities degree in the middle of a pandemic. Many of my friends were at a loss of what to do next, many did a Masters degree just to give themselves more time (thank god for student finance in my country being accessible). I was incredibly lucky, am still incredibly lucky to be working in an industry that is related to my degree and not become a teacher as so many do (the strongest of us ultimately).

I was almost glad it was quiet that first day not just because of pandemic fears but also because I was placed in the art galleries rather than the history ones where the history graduate in me would have flourished right away. Art was not something I knew much about. I had friends who were artists that I learned second hand what was ‘good’ art to them. I was so nervous someone would ask me a complicated question about some of the pieces on display (especially the modern ones!) so I spent the rest of the day going through every label and writing down names to research later, most of whom I had never heard of. To my shame one of these names was J.M.W. Turner. However, there was only one painting that I kept going back to, whose gaze I couldn’t look away from. Margaret Clarke’s portraits often stare out at the viewer in a way that demands their attention and this one certainly had mine.

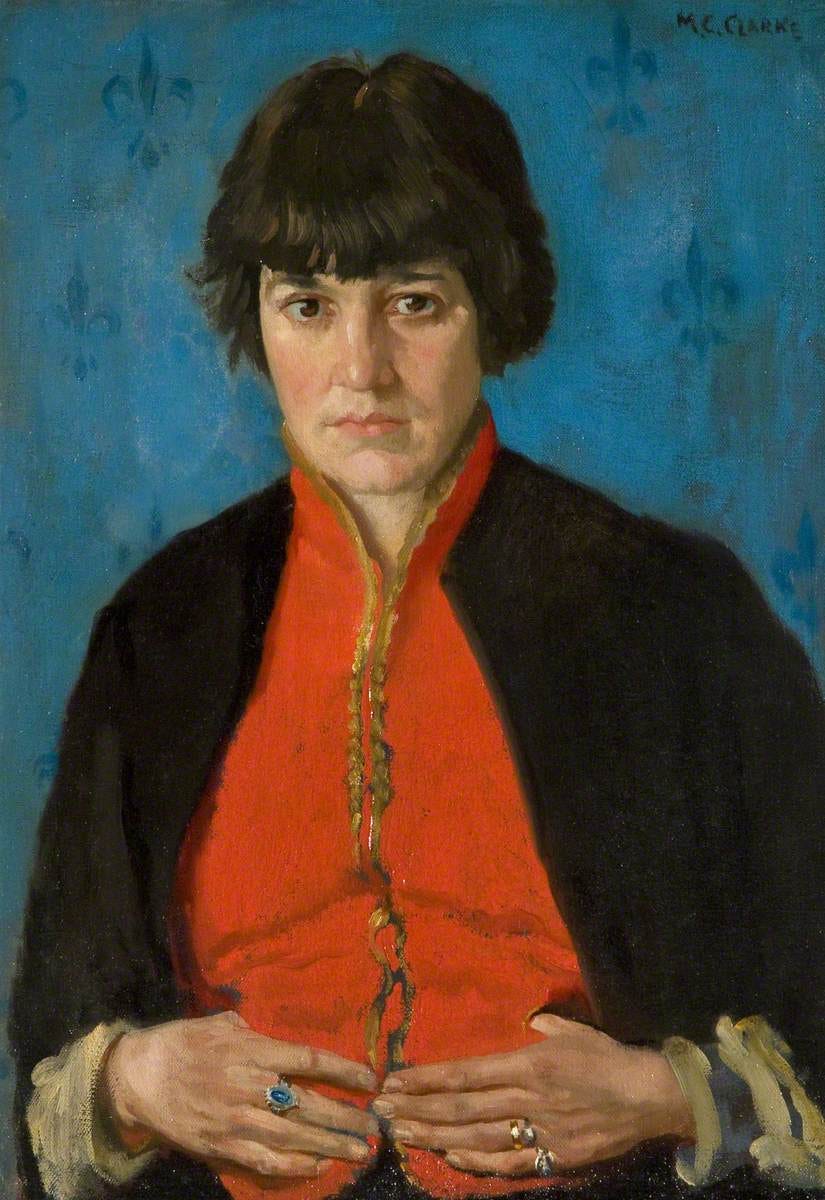

Self-portrait, 1914, Margaret Clarke. National Gallery of Ireland.

She was the only female artist on display in that room and even then the label noted her as famed stained glass artist Harry Clarke’s wife. Surely there was more to her life than that. Surely her skill existed before him.

Margaret Clarke was born in Newry, County Down, in the North of Ireland in 1884. Her family were keen learners and many of the children were encouraged to further their studies to create better careers for themselves. Margaret and her sister Mary trained to be teachers though Margaret had a special interest in art. She attended night classes at the local technical college and eventually earned a scholarship to the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art where she aspired to become an art teacher. During her studies she achieved many awards and scholarships and it was here that she met famed Irish artist William Orpen. As her teacher he recognised her skill and it wasn’t long until he took her under his wing and hired her as his teaching assistant at the age of 22. She would later take over his classes when he decided to move on.

She married fellow student Harry Clarke in 1914 and it was around this time that she was spending summers in the Aran Islands, painting and sketching the residents and scenery. Margaret’s art thrived alongside supporting her husband and eventually their three children but it was still often a struggle. Harry suffered from tuberculosis and would often go through periods of poor health that required Margaret’s art to sit on the back burner. Harry owned a stained glass studio that became more and more popular as his unique skill was recognised and often Margaret helped to keep it running when his health failed. It is possible to see the influence of the stained glass work on her paintings, the richness and combination of colours beginning to shine through her work. Margaret was elected as a full Academician of the Royal Hibernian Academy in 1927 and was the second female artist to have done this, the first being the wonderful artist Sarah Purser.

Ann with Cat, circa 1924, by Margaret Clarke. Copyright artist’s estate

Sadly, four years later Harry died at age 41 when coming back from a stay in a sanatorium in Switzerland, he never made it back to Ireland and was buried there. Even more devastatingly is that he was later relocated to a communal grave due to misinformation being given to his family about maintaining his grave. Not only did she spend much of the rest of her life trying to protect and advocate for the work of her husband but also that of Mainie Jellet who I wrote about a few months ago. Margaret was also getting a significant number of commissions that would make her famous in her own right during her lifetime if not so much afterwards. She died in 1961 and for many years her work was then overshadowed by the tragic figure of her husband. The National Gallery of Ireland has done a lot of work in recent years to rectify this. In 2017 they opened up an exhibition called An Independent Spirit that showcased the outstanding work that Margaret had completed in her lifetime and the development of her skill through the phases of her life.

Robin Redbreast, c. 1915, Margaret Clarke. National Museums Northern Ireland.

One of my favourite paintings of hers is Robin Redbreast. I am enamoured with the detail she has put in, the glint of the rings on her sister Mary’s fingers, the stereotypical male stance that has been adopted, the cropped cut of her hair and the fantastic red of her waistcoat. To me it’s a painting that tells a lot about women in Ireland at that time. How gender was being viewed differently with the suffrage movement and Irish women’s involvement in Ireland’s fight for independence. Some believe that Mary’s gaze is hesitant, maybe it's the dip of her chin that makes people think she is lowering her head. I think it is an arresting gaze, a demand to take me as I am, a no nonsense look. Or maybe the more I look at it the more I can imagine Mary’s hesitancy seeping away as she becomes comfortable as the sitter. That’s the wonderful thing about art. It can mean anything and everything.

There is a fantastic lecture that is available on YouTube for anyone interested in hearing more about her done by the curator of the exhibition in the National Gallery of Ireland -

And I really enjoyed reading this Irish Times piece on Margaret Clarke and the exhibition - https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/art-and-design/visual-art/margaret-clarke-s-portrait-work-steps-out-of-the-stained-glass-shadows-1.3073038